"I think the astronomers of the first years of the twenty first century, looking back over the long transit-less period which will then have passed, will understand the anxiety of astronomers in our own time to utilise to the full whatever opportunities the coming transits may afford...; and I venture to hope... they will not be disposed to judge over harshly what some in our own day may have regarded as an excess of zeal."

Richard Proctor, Transits of Venus, A Popular

Account, 1875

The

Story of How I Went to

Motivation:

What did I want to go see, and why did I feel such a yearning to observe it? Did I suffer from my own “excess of zeal?” A small black dot on the face of the Sun barely seems like a spectacle even worth stepping outside of one’s home to see, let alone one worth traveling thousands of miles. Its only special excitement seemed to be its rarity. The last transit of Venus occurred in 1882, which is so long ago that it had been true for some time that no living person had ever witnessed such an event. But many millions of people would be observing this year’s passage of the planet Venus across the face of the Sun, and many of those people would have excellent telescopic equipment at their disposal. If I went to see it, what observations could I contribute that would be unique?

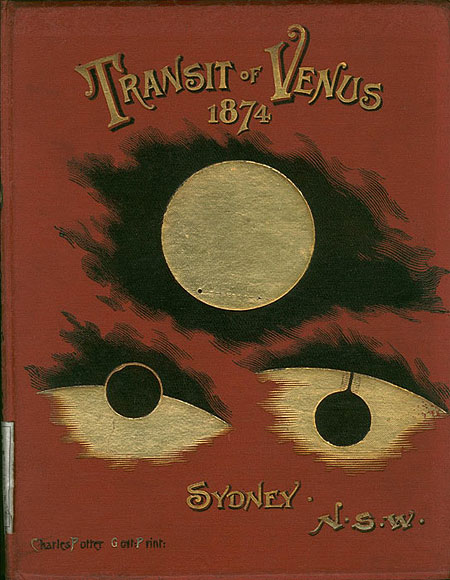

I really had to think about that one. Almost all of the zeal for observing Venus transits in centuries past stemmed from how well these events could be used to determine the distance between the Earth and the Sun, and thus measure the size scale of this Solar System of sun and planets in which we find ourselves. Before the Venus transits of 1761 and 1769, nobody knew just how far away the Sun really was. After those transits, they figured that the average distance was roughly 95 million miles. The more recent transits of 1874 and 1882 helped refine that figure to closer to 93 million miles. But the 20th Century saw the use of interplanetary radar signals and actual spacecraft voyages, and these measured the distances between planets to far greater accuracy than any measurements of a Venus transit could ever hope to do.

So a Venus transit today is just something that’s kind of neat to watch, with an added touch of historical interest. There isn’t much new scientific knowledge that can be extracted from it-- that is, unless you have a very large telescope and special non-optical or spectroscopic equipment. Yet observers of transits past have described some unusual effects that have not been trivially easy to explain. One of those effects, the so-called “black drop effect,” also profoundly frustrated those pioneering transit observers because it ruined the timings they were trying to take. By 2004, astronomers thought they could explain why the black drop effect happened, but modern day observations would still be needed to confirm these theories. Maybe I could help check it out.

The Scientific Goal: (You can’t have an expedition without a goal.)

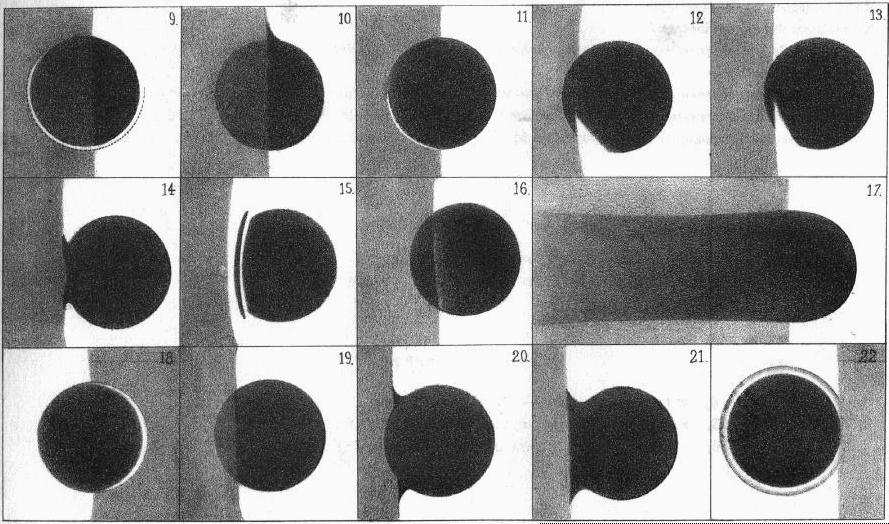

What is the “black drop effect?” I’ll answer that by showing you some sketches from the transits of the 18th and 19th Centuries. When Venus appeared near the edge of the Sun, its silhouette appeared to cast some interesting shapes:

While fascinating, I’m sure you can also appreciate how annoying these effects were to anyone who wanted to know the exact time when Venus passed fully in front of the Sun’s disk. Just imagine Captain Cook, having sailed all the way from England to Tahiti to clock the 1761 transit, anxiously asking his assistant, “Is it in?” and hearing the reply, “I’m not sure!” This lack of certainty went on for more than half a minute, while they had hoped to time Venus’s ingress to within a second’s accuracy.

Most of the above drawings almost certainly result from astigmatism in the observer’s eyes, faulty telescope optics, and optical illusions. But the sense of Venus “dripping” onto the face of the Sun was reported, to some degree, by nearly all observers, so it can’t all be bad optics. Some of these problems will not go away, no matter what.

This next picture illustrates the most significant cause of the black drop effect:

Light from the Sun appears to extend beyond the true edge of the planet and also beyond the true edge of the Sun itself. This is referred to as “irradiation” of the sunlight. The above drawing shows sunlight appearing to originate from inside the true limb of the planet. The effect of irradiation is especially strong around Venus because the atmosphere of the planet also acts as a lens to refract the sunlight inward. But a weaker version of the black drop effect is still seen in transits of Mercury (a much smaller globe that transits the Sun’s face much more frequently than Venus), and Mercury has no atmosphere to bend sunlight. Planet atmosphere or no planet atmosphere, the irradiation of sunlight happens because no picture of the Sun can be perfectly sharp. The slightest fuzziness of the image spreads the sunlight out beyond its proper borders. The black drop effect is seen when the apparent limb of Venus is completely inside the Sun’s apparent limb, while the true limb of Venus remains outside the Sun’s true limb. The bigger the difference between true and apparent limbs, the more dramatic and longer lasting the black drop effect becomes.

The fuzziness of an image is called its “resolution”-- it’s a measure of how sharply focused an image appears. Air turbulence is usually the main factor that blurs what you can see through a telescope. Astronomers refer to this fuzzing out of images due to unsteady air as “seeing.” When the seeing is good, the view is sharp, crisp, and detailed. When the seeing is bad, it’s like trying to look above black asphalt on a hot summer’s day. The images shake and shimmer, looking quite fuzzy. A swimming pool analogy is a good way to understand the problem. If we looked at the sky from the bottom of a swimming pool, the blurriness would be far worse. Yet, on Earth, we live at the bottom of a deep ocean of air, and we must look through this unsteady air whenever we look at the stars above our heads. Bad seeing is what causes stars to appear to twinkle at night. Without Earth’s turbulent atmosphere to mar the view, there would be no twinkling.

Some other things are also believed to contribute to the black drop effect. I already mentioned the inward bending of sunlight by Venus’s atmosphere. The thick and cloudy atmosphere of Venus also gives the planet a naturally fuzzy edge to begin with. The same can be said of the Sun itself, for the Sun is a great ball of gas that lacks a sharp boundary. Also, the limb of the Sun appears somewhat darker than the center because we are not looking as deeply inside the Sun when we look at the Sun’s edge. This “limb darkening” might enhance the appearance of a drip as Venus first crosses the Sun’s edge.

So… I managed to scrounge a meaningful scientific mission out of all of this: Observe the black drop effect, take detailed digital photographs that can be analyzed pixel by pixel, and compare my observations to the published theoretical explanations that explicitly model all of these effects.

Getting Ready for the Trip:

Okay, great. So now I

just had to find a good place to view the transit. Most readers probably already know that the

transit of June 2004 was not visible from

However, not everyone who stood in those areas actually got

to see anything at all, even if they had the right viewing equipment with

them. Cloudy weather was sure to affect

the view adversely from most places. I

needed clear skies; and if was going to travel all the way to another continent

and spend that much time and money on this project, I really needed guaranteed

clear skies! Insisting on better than

99% certainty of cloud-free weather ruled out most of the possible locations

except the

Within

If anyone is wondering why I couldn’t use a bigger telescope deliberately set just a little out of focus, here are two big reasons: 1) When traveling across continents and oceans, I want something as light-weight and portable as possible. 2) When putting a telescope out of focus, it’s hard to know exactly how out of focus it is. Better to focus your telescope as best you can, and let the so-called “diffraction limit” of the telescope determine the resolution. This second point explains why my particular experiment was not something that other people could do with larger instruments. In fact, given how bad daytime seeing can get and how I had to have a telescope with a diffraction limit that was worse than the daytime seeing, I had a lot of trouble finding an appropriate telescope. I needed one that was small enough for my purpose, and yet not so small that the optical quality would be inadequate. (After all, telescope manufacturers don’t bother to invest their highest standards in the optics of itty-bitty telescopes.)

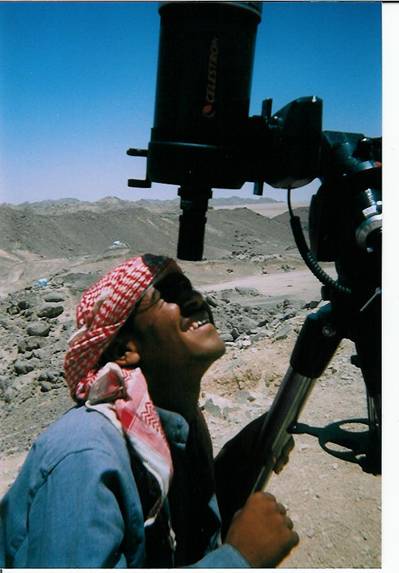

Considering all of the requirements, I figured that the front-end diameter of my telescope should not be larger than three inches. I also needed a reflector (mirror-based) design with industrial precision optics and a reliable object tracking system. Alas, there is no such beast with a small enough diameter. Instead, I ended up buying an excellent 5-inch telescope (a Celestron-5GT), and I covered the front of it with a snug-fitting plastic ring that reduced the effective diameter from five inches to three. (This also was not something I could have done with a larger telescope because reflecting telescopes have “secondary” mirrors in the middle of their front ends. The secondary mirror of the Celestron-5GT is just small enough to still allow a reasonable amount of light through when I inserted the ring to reduce the telescope’s front aperture to only three inches.)

The Celestron-5GT has a computer chip for automatic pointing (finding objects in the sky) and tracking (staying pointed on those objects as the Earth turns), as long as the telescope is properly aligned to begin with. It also has a connection to a global positioning (GPS) system that would allow it to align itself automatically, whenever and wherever it is switched on. That GPS connection was a strong selling point for me, but the company was backlogged on orders of compatible GPS systems, and I never received my promised GPS until nearly two months after my expedition was over. (Oh, well.) That made my transit observation a lot more awkward, since I needed visible stars to align the telescope myself and the stars are not visible in the daytime. Lacking a GPS meant having to first set up the telescope at night, then leave it continuously running throughout the next day.

Other required equipment included a strong tripod (obviously), a power supply, solar panels for recharging the power supply when out in the middle of nowhere, a laptop computer (which we already had) for storing digital images, and a special “filter” to put in front of the telescope to make it safe to view the Sun.

Turning the Trip Into a Family Vacation:

&& Getting my husband, Rich, to go along as technical assistant. (Rich knows much more than I do about how to get computers and other gadgets to do what they’re supposed to do.)

&& Securing time-share resort exchanges in

&& Planning ways to keep our 4-year-old daughter

Melissa entertained during the trip. (She’s the little girl riding with me on

the camel in the picture at the very top of this web page.) Inviting my sister-in-law

and her husband to join us in

&& Waiting weeks for the solar filter to arrive at home in California, having it reach California the day before we left but still not reach our home, and then having to order it sent ahead to Salou, Spain (where we vacationed before heading on to business).

&& Our travels in

All this time I checked with the desk

every day to see if the solar filter had arrived yet. It was supposed to have arrived on Tuesday or

Wednesday at the latest. Since we were

leaving for

And here is when I really really

wished that I had fully tested the camera setup before I left

Rich ran off to check out all of the digital camera stores

in Salou, while I stayed in the courtyard testing and

adjusting everything else. Always

wanting to do some public outreach, I invited some of the resort staff over for

a look at the Sun. The Sun looked pretty

boring that day-- just a few very small spots-- but I was able to explain to

the desk clerk (who was fluent in English) that sunspots were places where the

Sun’s magnetic field was so strongly concentrated that it stifled the outward

flow of energy (by suspending material in place) and that the small sunspots we

were seeing were nearly as large as the Earth.

While showing off the sunspots, I could see that the image quality was

excellent but that the telescope didn’t follow the Sun very well. That didn’t worry me, however. If I could have aligned off some stars

instead of just estimating north from a map, the tracking would certainly have

been better. In

Rich eventually returned with good news and bad news. The good news was that several stores sold

digital cameras with the necessary minimum capabilities of high resolution,

strong light grasp even with very short exposure times, and the ability to take

several pictures a second. These cameras

could all download to our laptop. The

bad news was that not one of these cameras fitted the attachments that we had

for mounting to the telescope. If we

were going to buy a digital camera here in

&& Off to

Since the camera set-up was now much less than ideal, I was no longer so concerned about getting up to high elevations. The thought of hauling all that equipment around on unknown mountain trails in the Sinai was also starting to weaken my resolve. Still, a plan was a plan. On Sunday morning, I was determined to reserve seats on the next day’s fast ferry to the Sinai. Besides, I knew that I could not stay on the humid seashore. I had seen how badly the stars twinkled our first night in Hurghada, so we definitely needed to move some distance inland.

The concierge had another idea though, and I jumped right on it. The resort offered an afternoon/evening “safari adventure,” taking tourists 75 km inland to a Bedouin camp at foot of the mountains. “Could we stay the night at the camp”, I asked, “and then get a ride back on the evening of the next day?”

“Okay! No problem!”

That was way too easy, but by then I was very much in the mood for easy.

As I type this, I still do not know if I will regret my

decision to stay that near to the

The Moment of Truth:

&& Story of getting out to the camp, meeting with the sheikh (chief) of the Bedouins, and getting the telescope set up and running on top of a high hill as it got dark. I should also say a lot more about the Bedouin people and how kind and helpful they were to us.

We returned to the camp and were directed to a place to sleep. Our hosts made us a “bed” outside under the open sky. They created this bed by laying two wooden benches together and covering their tops with blankets. The spot outside that they chose for us was right next to a rock that had been marked with red handprints. (We later learned that these handprints were composed of goat blood. There is an Islamic festival called the Eid ul-Adha, in which goats are slaughtered and their meat is shared with friends, relatives, and the poor and needy. Somehow, leaving a handprint in goat blood has become part of this ritual.) Our backs and hips felt quite sore and scratched up after we struggled for half an hour to get to sleep, so Rich troubled our hosts again for several pillows. We got prompt service with a smile-- but I suspected it was an amused smile, having a little laugh at these soft and wimpy Westerners who couldn’t sleep on a perfectly well blanketed bed.

The sky above us was gloriously clear and star studded. I couldn’t help scanning with my eyes over the rich textures of the Milky Way. It was also dark enough to notice the band of “zodiacal light”-- a faint glow of very fine dust particles confined to our Solar System’s orbital plane. Each time I awoke that night, the positions of the stars above me had shifted as the world had spun beneath the firmament. The amount of this shift told me how long I had been asleep: an hour here, two hours there, it can’t have totaled up to more than five. I did not get a good rest, but for some reason I did not feel particularly tired in the morning. The big day had arrived. That and the novelty of where I was had me wide awake, functioning on adrenaline.

Rich and I awoke together just before sunrise. Glancing up at the top of the hill, we could

see that our telescope was still standing.

Whew! (We’d been seriously

worried about wind gusts, wandering goats, and goodness knows what else.) We figured we’d head up right away and have a

look. We found it still tracking the

stars of Cygnus, even though those stars could no longer be seen in the rapidly

brightening sky. The air was calm; the

desert seemed beautiful (a rugged, ugly beauty that few people would

appreciate) and tranquil. We were far

enough inland that the

I had chosen a spot on the crest of the hill that would still be somewhat sheltered if any wind came blowing off the sea. But the wind came from the north, and it quickly began to strengthen as the desert ground began to heat. While the tripod firmly held its place, the telescope itself vibrated just a little and there seemed to be no way to prevent that. I could only hope the wind would die down when the Sun rose higher. That hope was never realized. It would prove to be a windy day throughout.

All the telescope’s high-tech bells and whistles proved their worth when I simply selected “Venus” from the control panel menu and the gears aimed the telescope almost directly at the Sun. Bull’s eye! The tracking also remained reliable enough that I would only have to make occasional adjustments throughout the day. We were all set, and the start of the transit was still nearly three hours away.

While we were up there, we watched three camels run at full speed around the base of our hill and off into the desert. As we had learned from our previous day’s tour, the Bedouins had been depriving these camels of water for three weeks. Mad with thirst, they ran out into the desert to find water. They seemed to know exactly where to go! From our high vantage point, we barely could see where they stopped several miles away and hoofed the ground. Two Bedouin men followed their tracks at a rather nonchalant pace, and appeared to bring them water as their reward for service (maybe… we’re not sure). Perhaps the Bedouins would later dig a well at the spot the camels selected.

We went back down the hill briefly to eat a little breakfast and socialize with our hosts as best we could before returning to the telescope about an hour before we expected the transit to begin. Rich wanted to use that hour for some more practice holding the camera just right. But as soon as I re-centered the telescope on the Sun, I spotted the black silhouette of Venus just starting to cut into the Sun’s edge. The moment of the black drop effect was just a few short minutes away!

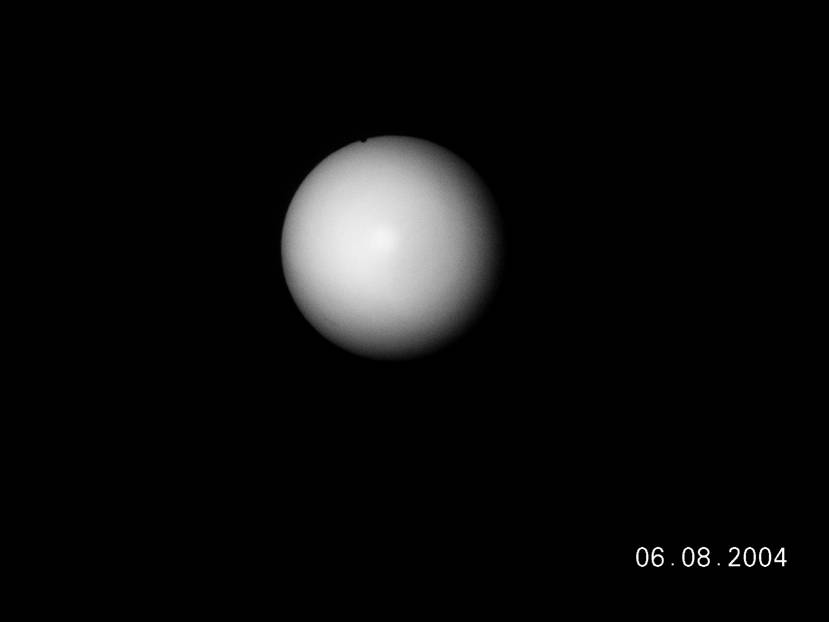

No time to take practice shots! No time to consider increasing the magnification or experimenting with any more of the camera settings. I had to yell at Rich to get over to the telescope and start taking pictures immediately. He hadn’t even turned on the camera yet!-- and the settings we wanted took a moment to initiate. No time for him to find his groove first. He just held the camera in front of the eyepiece and started shooting, while I stood right next to him and spread my body wide as best I could to shield the telescope from the roaring wind. The telescope was shaking, and I think Rich’s hand was too. Not surprisingly, most of those pictures weren’t the greatest; but Rich did get a few decent shots. Just so you can get an idea of when we started, here is the first photo of the day. (Venus is encroaching on the upper left.)

The seeing seemed to be excellent, despite the strong wind. The magnification setting was a rather low 39 x. The right edge of the Sun fades out in this picture because Rich hadn’t yet perfected the skill of keeping the camera perfectly aligned with the telescope. (That ultimately may have turned out to be a good thing, because we were later able to make some insightful comparisons between some of the not-so-good images we got and some of the problem images from the 18th and 19th Century.) Another issue was that the wind was pretty fierce, and I’d instructed Rich to concentrate only on the edge of the Sun where Venus appeared.

This next photo shows how the shaking of the telescope combined with the camera angle would sometimes affect the image. At least, we think that’s what caused a faint “horn” to appear in front of Venus in this shot. (Look very closely at the left side of Venus’s silhouette.) Perhaps something similar happened to cause some of the strange apparitions that a few of the observers from centuries past reported seeing?

If you ignore the effects of the doubled image, then this is also the clearest black drop effect that we saw at the moment of ingress. The effect wasn’t very dramatic, as you can see. Very shortly after this picture was taken, the effect completely went away as Venus moved to a position completely in front of the Sun. That was disappointing. Luckily for us, the black drop effect became much more strongly evident many hours later at egress; and by then we were better prepared.

Why did the transit start an hour earlier than I’d expected? Blame daylight savings time! I’d made the same mistake that I regularly catch my students making when I teach the astronomy lab class at CCSF. I was confused about what time zone I was in and which places were on daylight savings time and which weren’t, and I thought I had it right but obviously I didn’t! I sure was goofing up a lot on this trip! #kick, kick, kick#

So, anyway… As the transit progressed, Rich and I went back up and down the hill several times. Staying up on the hill became unpleasant in the intense heat and sunlight, but taking a cool breather down in the camp’s shady tents always meant having to climb all the way back up the hill again later. While up the hill, we would check that the equipment was still okay. (We were pleasantly surprised at how well the tripod held its place in the wind.) Rich had plenty of time to refine his technique for holding the camera steady to get good, sharp, well centered images. I also chose to increase the magnification just a bit (to 50 x) to improve the pixel resolution of the images; and, happily, Rich had very little trouble adjusting his practiced methods to match the new magnification setting. We were now just waiting around for “third contact,” when the black drop effect would show itself again.

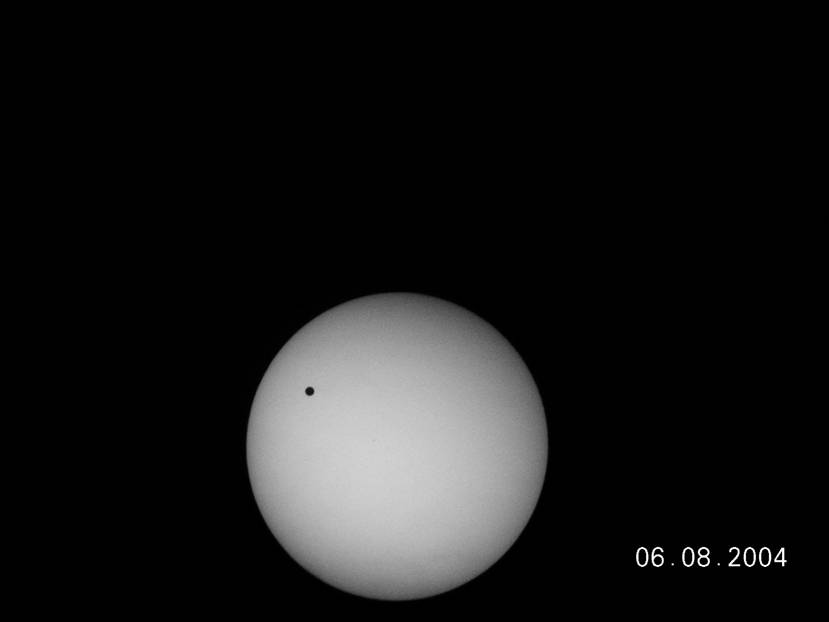

Here’s one of the pictures that we took at about mid-transit:

We had a total of nearly six hours to kill between second and third contacts. (“First contact” is when the transit begins, “second contact” is when Venus first crosses completely in front of the Sun, “third contact” is when it starts to leave the Sun’s face, and “fourth contact” is when it’s all over.) During that time, the Bedouins served us a yummy brunch of bread, beans, and goat cheese, and an even yummier late lunch of falafel. They also quenched our bottomless thirst with lots of tea and bottled water. We did compensate them for it, but they were being so nice that we felt that the least we could do was offer them a look at what we were doing… (even if that did mean going back up the hill again).

Most of the Bedouins weren’t interested enough to tromp all of the way up to the telescope in the very hot middle of the day, however. Only a few made the trip, but they seemed to appreciate the telescope view, and I did my best to explain what was happening with the help of a few Arabic words I had studied and also by making drawings in the dirt.

The hottest part of the day is also when a small group of German tourists dirt-buggied into camp, and I practiced my German by inviting them up the hill to see the Sun and Venus. Just one look at our hill and they also took a pass. So, while the Bedouins gave the Germans some camel rides, Rich and I sat in the cool shade of the biggest tent and watched an Arab boy (who’d accompanied the tourists) teach karate moves to two young Arab girls who had ridden with the boy on his dirt buggy. Only in this modern era of fast and easy travel and cultural exchange could such a sight be possible: a Bedouin outpost in the middle of the desert, with German tourists riding the Bedouin’s camels for fun as the children of their Arab guides learned Japanese martial arts techniques while two incidental North American travelers looked on.

Meanwhile, Venus continued its passage across the Sun’s face. To my great relief, the seeing seemed to holding steady as third contact neared. Most of the time the Sun’s edge still appeared as sharp as it had in the morning, but every now and then I would see the Sun waver and wiggle as we were hit by a burst of air turbulence. The wind gusts also continued, so the shaking of the telescope was still a problem. But we managed to cope, and Rich continued to shoot several pictures per second. Here’s one of those pictures:

And then it happened…

Notice the extra fuzziness around the edges in this shot. Apparently, this was one of those moments when the air turbulence picked up. That definitely exaggerated the black drop effect. We have many other shots, taken within a minute of this one, showing a sharper image with less of a black drop. It took bad seeing to bring this out. Here’s a close-up of the same shot:

Fairly soon after this, the black drop effect went away as Venus left the Sun’s face in a performance that was a simple reverse of the way it came. Then it was all over. Nothing more to see; nothing more to do-- except to pack everything up, bring it all back to the camp, and find out how soon we could hitch a ride back to town.

The above picture shows me (in the light blue shirt)

carrying one small piece of our equipment back down the hill after the transit

ended. Two of the Bedouins who were

helping us can be seen at the base of the hill coming back up for more. Beyond them is the camel pasture. One mother camel and her baby are fenced in;

the others roam freely but choose to wallow in pretty much the same spots all

day. Visible beyond the camels (if you

have zoom ability), you can also see a large pigeon house plus a rather small

pen for chickens, goats, and sheep. The one

spot of green vegetation in the middle of the camp is the sheikh’s personal

sanctuary, into which he invited us to relax and chat with him while we waited

for a ride back to Hurghada. (Despite the sheikh’s marginal English, we

managed to converse on topics as diverse as

&& Results wrap-up.

More discussion? Short description of the

rest of our visit to

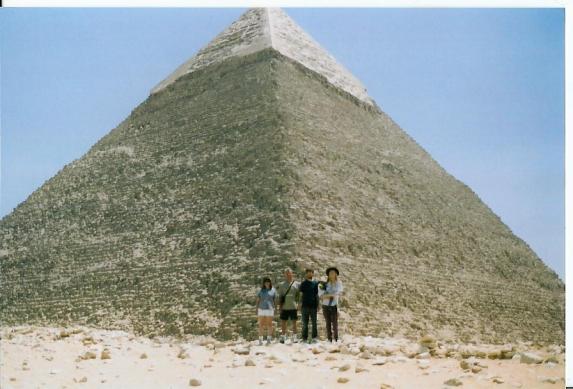

I’ll close with a couple of tourist shots that nicely

illustrate a very common problem that astronomers must face when they look at

objects in the sky. Below is a picture

of (in order from left to right) my sister-in-law, my brother-in-law, my

husband, my daughter, and me in front of the second largest of the pyramids of

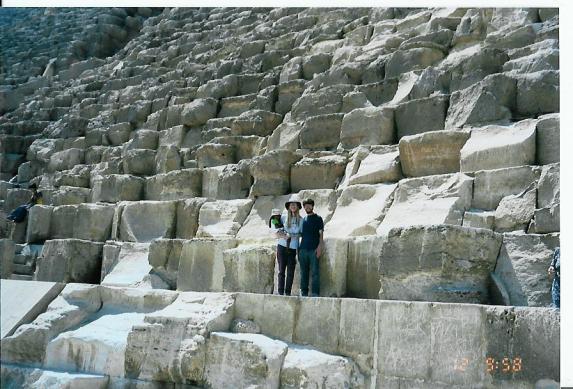

If you’re still not believing that this pyramid is really huge, here’s a different picture that shows us up against the building blocks:

This is the Great Pyramid (your awe and imagination should conjure up an appropriately inspiring fanfare). While I admit that this one is bigger than the 2nd biggest pyramid, the blocks are the same size, so this shows exactly what the other pyramid would have looked like if we really had been standing right in front of it. (And don’t those pyramids still look pretty good after more than 4,000 years of wear and tear?)