The YORB

In 1994 I visited New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program, headed by Red Burns. While there I met Nick West, who showed me a project called "The Yorb". "The Yorb" (short for "your orb") utilised telephones and cable television to deliver a weekly program which viewers could participate in using their telephone keypads and receivers. While watching the program, viewers could interact with the onscreen YORB environment, shown as a 3D computer generated space.

Click here to view

an interview with Nick West, coordinator of YORB, which I videotaped in

1994.

This project led me to consider the overall subject of urban planning and cities

as a theme in the development of 'multi-user' communities. This is a theme I

had been exploring while a researcher at Beam Software International between

1992 and 1994. Beam's design department had the job of organising graphics for

video games such that the player was engaged in an enjoyable passage through

imaginary environments. This involved the preparation of elaborate maps, which

depicted the possible places the player moved through.

1994: Raving with YORB

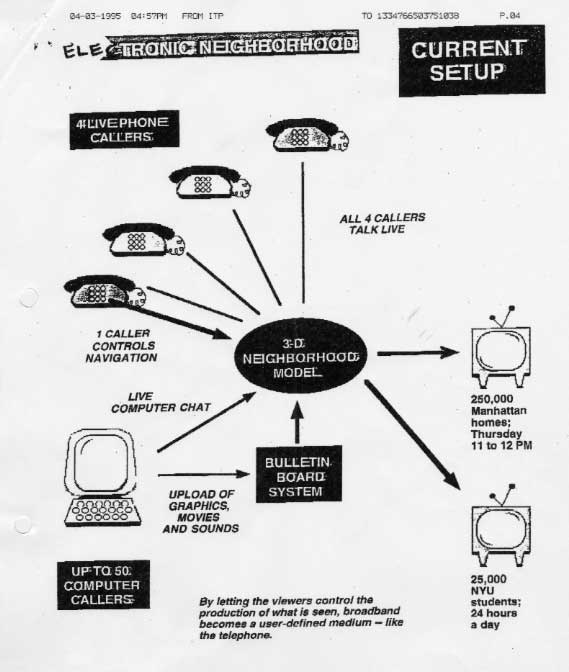

The Yorb was a television show broadcast by the New York University’s (NYU) Open Telecommunications Program (ITP). It transmitted computer graphics of a cartoon-like 3D world, which could be interacted with and ‘navigated’ by viewers using their home telephone numerical keypads.

YORB coordinator Nick West, who showed me the YORB system while I videotaped his commentary in 1994, explained its simplicity. He told me that the system was essentially two power Macintosh 7500s triggering laserdisc rendered animated sequences of city ‘drive-throughs’ by means of telephone keypad tones. The 3D cartoon ‘city’ imagery on the laserdiscs had been created on Amigas and Macintoshes and showed a world of wild signs and buildings.

Sudden motions down streets were interrupted by pauses as the computers interpreted telephone keypad dial tones and then turned them into laserdisc chapter playbacks. The YORB was staged every Friday night in New York, and according to Nick West, attracted an audience of between 2500 and 4000 participants per week. YORB users could interact with the world in one of the following ways:

a) via telephone keypad entry by YORB users from home. These could trigger events within the city. A given caller could ‘drive’, while others could operate other events (e.g.‘play’ a musical instrument, or open a door etc)

b) via bulletin board. Viewers could dial up to a YORB bulletin board via modem, and once connected type commentary to a scroll bar which would appear as part of the broadcast at the bottom of the screen.

c) via telephone voice

Click here to see a complete faxed design for YORB sent to me at RMIT by Nick West at NYU in 1994

The YORB experience was also similar to a radio talk back show, as viewers could telephone, not only to control the TV environment, but also to add their voice to a mélange of voices added to the live ‘mix’.

This hybridization of media forms: telephone, television, radio talk back, nightclub DJ, bulletin board etc was very much at the core of the idea – a multifarious, deliberately busy, noisy community event. Like New York itself, the YORB was a lively, ongoing, bustling phenomenon.

YORB broadcasts were held on Friday nights at about 11pm and were generally short (about 20 minutes) and featured frenetic activity. Computer users could upload text commentary to a bulletin board based at the ITP, with the messages appearing in a scroll bar at the bottom of the screen.

I wrote an article about the YORB for my then regular column in the "Age" computer supplement "Frontier Media"

When I made a return visit to NYU ITP in 1998, the shift of the program was no longer toward television and telephone communities, but toward personal digital assistants assisting people’s navigation of the streets of New York.

The original YORB project was no longer being broadcast. NYU ITP research seemed to have become more focused on the individual, helping him to guide his way through the actual streets of Manhattan (with the help of a palm top computer and a wireless Ethernet connection and GPS co-ordinates).

The emphasis away from a deliberately contrived and fun neighborhood community interactive television service might have reflected changes in funding for the project. The YORB had been backed by the East Coast telecommunications company NYNEX as a trial for commercially based interactive services. It is most likely that this funding was withdrawn, or expended by the 1998.

Whatever the reason, I felt that the more corporate, privatized notion of the city mediated by global positioning sensors to benefit the businessman WAS A far cry from the celebratory, rave-like aesthetic and community ‘down-home’ appeal of the YORB.

The YORB in contrast to the personal navigation approaches which evident at ITP around 1998 can be read as also reflecting an ever-increasing privatization of the city of New York itself.

Why Cartoon Space for YORB?

The brightly coloured cartoon-like imagery that characterized the YORB was typical of the ‘techno’ aesthetic in the early to mid 1990s, typified by the type of graphics created by Melbourne artist Troy Innocent.

Cartoons and online communities share something of a common history, as do highly iconic designs of the surf, skate and garage punk aesthetic of California’s ‘grunge’ culture. Online communities often share the utopian aspirations of open minded, creative people, so it is fitting that the graphical sensibility of the YORB should reflect the utopianism and inclusiveness of the ‘techno’ music underground.

The real gift to New York City of the YORB was its appeal to the notion of ‘neighborhood’ – a traditional and strongly valued concept in New York City. New York City has a very high population (about ten million people) who live very close to each other and where space is at a very high premium. To replicate New York’s notion of localized and intensely lived communities in electronic form made the YORB very much the product of that particular city.

The users of YORB would, at home, while watching the show via cable TV, wait in a phone queue to join in on the onscreen action. This might enable the numbered keypad of the home telephone to determine the direction of the 1st person view of the cartoon like 3D world (actually a number of pre-rendered 3D computer graphics playing live off a laser disk player of a virtual city designed by artist Twin). Another type of interaction might be a section of YORB called "Ritual Ground Zero". In this area, users could choose between one of four on-screen musical instruments, and ‘play’ these via the touch buttons on the home telephone.

I considered the community mindedness of YORB extremely

progressive, and wished to replicate the idea upon return to Melbourne. I was

particularly impressed by the deliberate use of simple domestic home devices

in the project – particularly the idea that the telephone keypad, so often

used to simply navigate through phone queues while waiting for corporate or

retail services. Lacking the backing of a NYNEX however made implementing the

idea difficult.

1994 and 1995: Attempting to Replicate the YORB in Melbourne as EMU

The first step was to try to reproduce technically the system at NYU. It soon became clear that the only way to do so would be secure funding or in-kind support from the telecommunications giant Telstra as NYU had done with NYNEZ. Telstra Strategic Research Staff (based at the Telstra building in Exhibition Street, Melbourne) were approached, and following a high profile meeting with key personnel, Robyn Williams, John Bird and myself, Telstra finally declared themselves unwilling to offer resources without being able to claim 100% intellectual property for themselves.

Optus, a rival telecommunications company to Telstra, (with its head offices based in the USA) were considered, as they were experimenting with cable TV services. The term "interactive TV" was commonplace in 1994, 1995 and 1996, as cable, telecommunications, media and government jockeyed for position in what appeared to be an explosion of innovation in the world of communications. Then post graduate student John Power joined me in early representations of the EMU city space, as it would have appeared as a series of rendered spaces for use over cable television stations, in the manner utilized by the YORB at NYU.

The city was prepared using 3D Studio Release 4 software, and in its organic

and nonlinear look-and-feel resembled a city made up of vegetables, the whole

scene enshrouded in mist. When negotiations with potential broadcasters of the

EMU city project broke down, the idea was eventually abandoned altogether as

impractical, and outside the possibility and resources of AIM alone.

Early Interactive Television Experiments

In 1995 RMIT Animation and Interactive Multimedia post graduate student John Power and I developed 3D graphics of a proposed 'city' which was designed to be later integrated into a laserdisc program for use in interactive television. Due to events beyond our control, this original EMU video footage was lost.

In 1996 the Prime Minister viewed the EMU TV demonstration while on an official visit to RMIT's Animation and Interactive Multimedia Centre

Given that 3D graphics enable the creation of city space non limited by the conventions of real space, we decided that the space could appear as fanciful as we wished. The original EMU city was a fly through of an organic looking city, where many of the structures resembled organic matter, such as capsicums and other vegetables. Shrouded in mist, the city never made it past the 'fly-through' stage. The files related to the project disappeared toward the end of 1994.

The rationale was to render a series of 3D graphics "fly-throughs" to then integrate these into an interactive laser disk which could be operated via phone line remotely and broadcast via television. At the time the telecommunications company Optus was considered as a delivery system for the project as was an emergent cable service to be provided by Telstra. Neither avenues proved fruitful, and the decision was made to abandon the EMU TV project in favour of a world wide web based solution. The latter became the EMU WEBGRID

Viewers would watch the city space on television, and call a telephone number. If the caller was successful in getting through, they would then be able to use the keypad on their telephone to effect events in the broadcast 3D world. More than one person at a time would be able to dial up the service, and each person would have a separate set of tasks which could be performed using their own telephone keypads. The system would employ devices which convert different touch tone phone signals into electronic programmed events triggering pre-rendered laser disk based animated sequences (see diagram below).

Diagram shows the original 1995 EMUTV proposal, based heavily on the NYU "YORB" idea.

Lisa Webster article on the YORB

Comparison of the original EMU TV show idea to subsequent EMUWEBGRID:

Similarities: Both the original EMU TV show and EMUWEBGRID

share the idea of building a community from the participation of those using

it. Both make use of the city metaphor in doing so. One makes use of broadcast

paradigms and tools while the other is centrally Internet-based. Both make use

of digital graphics to represent the ‘urban space’

Differences: EMUWEB GRID relies on asynchronous participation (users log on at different times), and geographic distance between users (users are spread across the globe) , while EMU TV would have involved synchronous communication between people who were relatively close to each other in the ‘real world’ (they share the same physical city space).

EMU TV is largely analogue in terms of delivery and interactivity, except at

the actual generation of the 3D city and the switching which happens centrally

at the ‘server end’, whereas EMUWEBGRID is totally digital. With EMUWEB

GRID, the map of the terrain is the same as the territory – the dots are

representations of as well as being actual ‘home’ positions.