- Petersburg in 1915.

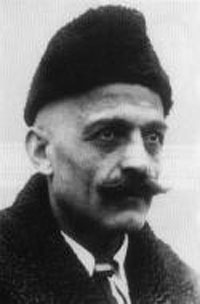

- G. in Petersburg.

- A talk about groups.

- Reference to "esoteric" work.

- "Prison" and "Escape from prison."

- What is necessary for this escape?

- Who can help and how?

- Beginning of meetings in Petersburg.

- A question of reincarnation and future life.

- How can immortality be attained?

- Struggle between "yes" and "no."

- Crystalization on a right, and on a wrong foundation.

- Necessity of sacrifice.

- Talks with G. and observations.

- A sale of carpets and talks about carpets.

- What G. said about himself.

- Question about ancient knowledge and why it is hidden.

- G's reply.

- Knowledge is not hidden.

- The materiality of knowledge and man's refusal of the knowledge

given to him .

- A question on immortality.

- The "four bodies of man."

- Example of the retort filled with metalic powders.

- The way of the fakir, the way of the monk and the way of the yogi.

- The "fourth way."

- Do civilization and culture exist?

|